Greeting Cards in between the 1920s Letters

Wedged in between the 1920s letters were three valentines to Pappy, a nickname for Charles. Even though none were dated, I assumed they were from the 1920s. However, it is more likely that they were from February 1943.

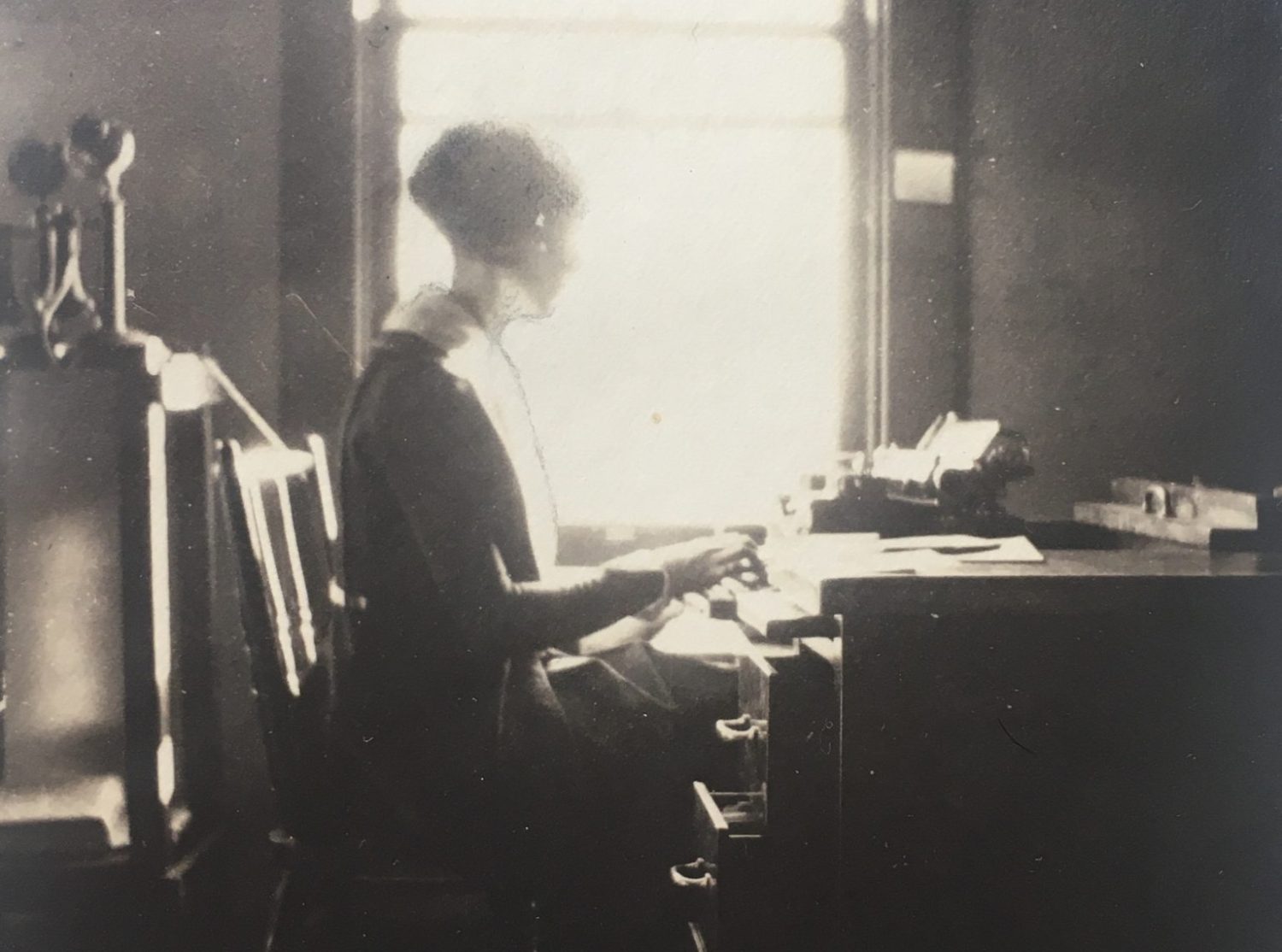

We learned in Helen Hemlin – Episode 6 (at 4:10) that Charles stepped away from his self-described “Vice President of Screwballs” writer job at the New Yorker in September 1942 to begin basic military training. His Officer Candidate School training commenced from approximately December 1942 through March 1943. Helen remained in New York during this time.

The Valentine’s cards from “Shawn” to his “Pappy” reminded me of Jorge and I giving cards to each other from Scout on holidays as well. Cards have been a monthly exchange between us for over 150 months in our relationship. I don’t recall how it started, but every month on the 25th, we celebrate being together. Perhaps someday those cards and their history will be relevant to the project. For now, that task goes on the For Later List.

The segment including Seán’s Valentines was appropriate as Valentine’s Day and Episode 7 coincided.

Remembering Charles

What I remember of my grandparents continued to drive my curiosity into Episode 7 and evolved as I worked backwards toward the 1920s letters. With Charles, the answer was relatively easy because I remembered very little of him. I vaguely remembered two visits to Cooperstown when I was less than 10 years old. And, one of those visits was Charles’ funeral in 1977. I learned more about him from the obituary I found in the collection than I had ever known.

Charles’ importance was simple. He was important to Helen, therefore he was important to me.

For example, over ten years after their marriage, Charles had joined the Army Air Corps and would join World War II as an officer. Helen wrote of the significance of having her wedding ring engraved:

Darling, it is beautiful. It says, ‘Charles and Helen, January 29, 1931.’ I had no idea having it engraved would make such a difference in the significance of the ring. It was always a symbol of our marriage and love, of course. But somehow now, these words engraved in the ring on my finger make me feel as though your very own warm hand were placed in mine in a deep bond of love.

Helen Cooke to Charles Cooke, September 8, 1942

More of What I Remember of Helen

Learning always accompanied memories with Helen. At the National Air and Space Museum, I remembered gazing upward at planes like the Spirit of St. Louis. I could daydream about flying around the world all afternoon. I didn’t have an ambition to be a pilot, but I liked being among the clouds floating what I imagined was free like a bird…a light breeze carrying me along.

The orderliness of the Changing of the Guard at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington National Cemetery so fascinated me, I asked to wait so that we could watch it again. What a coincidence that decades later I would find the pictures of Helen’s role in reviving the Air Force Officers’ Spouse’s Club (AFOSC). (See Episodes 2 and 3). Part of the club’s mission through the AFOSC Arlington Committee is to ensure no service person is ever buried alone at Arlington Cemetery.

It was not until writing this post and researching where I might have seen Mary Cassatt’s work, that I remembered slipping off my sandals and dipping my feet in the Mellon Memorial Fountain in front of the National Gallery of Art. Arlington summers were also memorable for their hot, muggy afternoons best suited to lemonade, a hammock, and a book. Cool feet, perhaps before or after I saw Cassatt, were to ingrain a memory of Helen present and available anytime I dunked my hot, tired feet into a cool mountain stream after a day of trail running.

I remember buying a print of ‘Child in a Straw Hat’ with my own money earned from odd jobs. Cassatt’s soft pastel works reminded me of the learning-rich summer days in Arlington with Helen. In 1996, I dabbled in pastel work for a class at Columbus College of Art and Design. My only work in pastel, a still life, included ‘At the Theater (Lydia Cassatt Leaning on Her Arms, Seated in a Loge).’ It hangs in my studio today, another reminder of Helen’s influence on my creative life.

These memories are not so much a longing for Helen as they are for the spirit of her presence. Who doesn’t need a reminder to listen to themselves, even if it is only for a few seconds a day? I wish that for every being.

1920s Letters between Helen and Charles

The first signs of a relationship between Helen and Charles were two 1920s letters. The tone of the first letter is friendly and led me to believe they may have been friends at this point.

Dear Helen,

I got your letter. I’ll come up to 115th Street at about 8 Monday evening – I’ll be mighty glad to see you again. The last time was 1901 wasn’t it?

Did I tell you I have another market for my stuff, namely ‘Life’? Probably I did.

See you Monday,

Charles

Charles Cooke to Helen Hemlin, July 26, 1929

The second letter in August 1929 implies that he and Helen had seen each other over the weekend. His handwritten letter confirms his arrival in New York and reveals his excuse to his boss for being late.

Dear Helen,

Arrived with no bones broken – at 10:40 – Ok with boss – told him my train was 1 1/2 hours late, rather than that I missed it – sounded better. My best to Beula and Jay, and of course to you.

Charles Cooke to Helen Hemlin August 19, 1929

I had no idea who Beula and Jay were. But, because Helen received the first letter at Clover Brook Farm, both recording studios and home of Lowell Thomas, I speculated that they might have been the writers Helen joined that May. That research item was already on the ‘For Later List.’

More of what I know of Charles

It was easy to research Charles’ work at The New Yorker during this time. By August of 1929, he had been with The New Yorker since May and had published eight articles, six for Talk of the Town and two Comments. His obituary quotes a James Thurber observation of him years later:

No other reporter equaled his energy, or came close to his output.

James Thurber on Charles Cooke’s writing for The New Yorker

I found no book by James Thurber titled, ‘Talk of the Town,” as referenced in Charles obituary. However, Chapter 5 of the 1962 edition of Thurber’s The Years with Ross is titled ‘Talk of the Town’. Page 106 not only includes the quote, it also notes that Charles was hired at $39 (about $600 in 2021 dollars) a week.

1929 Relationship Status: It’s Complicated

My excitement for finding what appeared to be the spark of romance between my grandparents quickly cooled as I fingered through the rest of the 1920s letters. Finding no more from Charles, the two dozen from various men relieved me. None seemed to gain enough of Helen’s attention to interfere with my grandparents falling in love. It was a bizarre anxiety given that I already knew they were married in 1931 and I also knew that they divorced in 1956.

Despite this knowledge, I was inexplicably irritated by a man named Howell. From October 1928 through December 1929, he wrote twenty-six letters. By the end of them, I not only couldn’t understand what Helen saw in him, I was ranting to Jorge about him.

But, I’m getting ahead of myself.

Enjoy the episode and please remember to like and subscribe. Thank you for following Another Thousand Letters.