Attention to Detail

In Episode 4, I unpacked the contents of the last two boxes from my family’s storage unit. The boxes had originally held chemicals for Dad and Arlene’s pool on Sheep Ranch Road in McDermott, Ohio. It was the same property where my siblings and I burned what we didn’t save while clearing out their home. (See Episode 2 – Unpacking Surprises.)

Had we opened boxes that actually contained pool chemicals and used them on our arrival in 2018, we would have killed a rich biological wonder. The pool’s liner had pulled away from the edge where it had been neatly tucked for decades. The water was so black both inside and behind the liner, you couldn’t even see a bee struggling on the surface in order to rescue it.

I avoided the rave of partying frogs, turtles, tadpoles, snakes, and mosquitos. In the meantime, my imagination concocted a rich compost of leaves and dirt underneath deadly, murky water. I feared the pool ruined.

I felt what I imagined Dad’s disappointment had he seen the property in its state. He was meticulous in caring for it, especially his lawn. We mowed the lawn but stayed away from the pool. It was too deep.

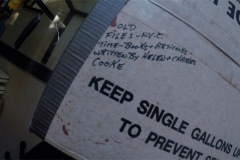

Three years later, I stared at Dad’s neat, all caps handwriting on the last two boxes. It reminded me of his careful attention to detail; opening the boxes would require mine as well.

Writers: Helen and Charles Cooke

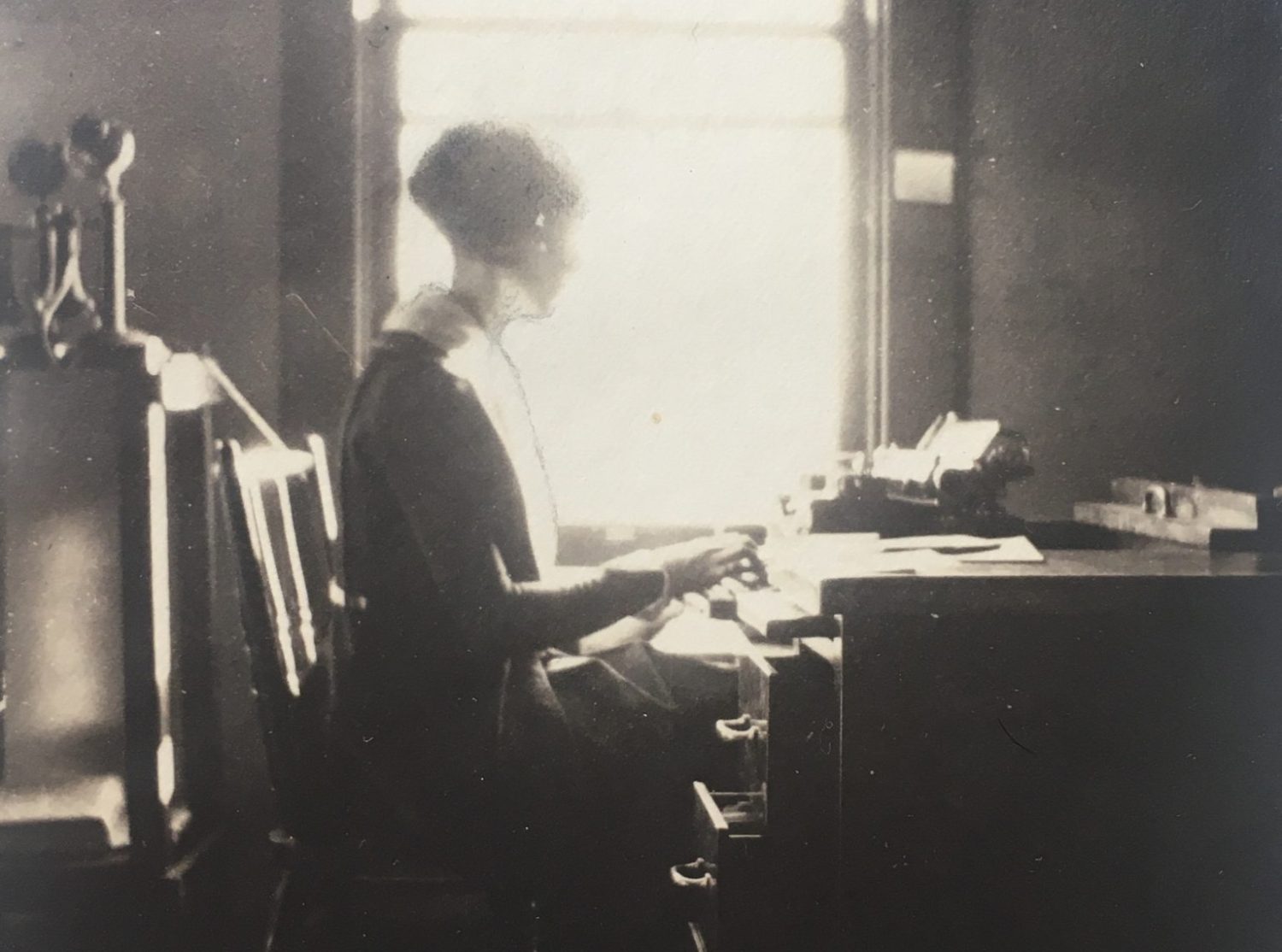

Helen grew up in Queens and Charles in Cooperstown, New York. With some context I didn’t have when I published Episode 4, both seemed destined to be writers. Helen’s education began in 1914 with a college preparatory certificate. She went on to study at University of New Mexico and Columbia University.

I always knew Helen as a writer who encouraged all things writing. During my visits with her in Arlington, I often curled up in a chair outside reading. Or, she would let me help her edit galleys. Sometimes I wrote stories and she would listen as I read.

I had forgotten some of these things.

Charles grew up under the influence of a literary family and a city known for a person many consider America’s first novelist: James Fenimore Cooper. Charles’ father, Joseph “Joe” Cooke, was also a writer. Joe does not appear to have had the success of late 19th and early 20th century writers like Cooper, but does appear to have been within its circle of influence. In a letter I later opened from Charles to Helen, Charles recounted getting his Dad:

going too on the days when he knew O. Henry – Dad and O Henry were then both having their stories published in Gilman Hall’s magazine [probably Ainslee’s Magazine 1897 – 1926], O. Henry a sensational success of course and Dad getting a story published now and then – Gilman Hall was always a great friend of Dad’s and it was he who gave Dad the unfinished manuscripts of O. Henry to finish after O. Henry’s death.

April 23, 1930, letter from Charles Cooke to Helen Hemlin (later Cooke). Another Thousand Letters collection, Boulder, Colorado.

According to the Greensboro History Museum’s summary of O. Henry’s papers, both Whirlygigs and Sixes and Sevens were published posthumously. I added a row to my “For Later” list to investigate this further.

Leather Bag of Letters

The Army-green, leather bag was stiff. I unzipped it carefully and even more carefully pried out a dozen letters Helen wrote and Charles had saved. Almost all were missing an envelope. Charles had folded into thirds each 8 1/2″ x 11″ piece of unlined paper filled with Helen’s words. A letter dated January 31, 1943, expressed Helen’s excitement to complete all her work “this time,” so that she could relax on their visit.

It struck me that “this time” meant that there had been prior visits where she had had to work. So much for remote working being a modern invention. Not so for writers!

I would later learn that in January 1943, Charles was training toward an officer commission in the Army Air Force in order to serve in World War 2. His gap in articles published at The New Yorker between October 3, 1942 (Comment on Key Hoarding) and March 27, 1943 (Distraction) was one hint of the intensity of basic and officer school training.

Key Hoarding & Phone Answering Dog

Recognizable topics surprised me while writing this Episode 4 post. I poked into the articles on either end of Charles’ military training. His perspective on hoarding door keys seemed as relevant today as it was in 1942.

…We have accumulated … many door keys … Our nerves have always been taut with the subconscious realization that many people undoubtedly have keys which would open our office, our apartment, our car, our filing cabinets, and our gymnasium locker. At the same time, we have derived no satisfaction whatever from the fact that we could open their office, apartments, etc. Key-hoarding is wholly irrational, and probably can be explained only by recourse to Freudian psychology…

The New Yorker, October 3, 1942 (Comment on Key Hoarding)

Jorge and I cleared out all our keys two years ago. We’d have little to contribute.

However, his topic, a dog who answers the phone, in Distraction sounded more and more familiar as I read the summary.

… a Kerry blue dog who likes to chew leather and answer the telephone. (He picks up the hand part of the phone in his teeth.) Usually the telephone is put out of his reach, but every time it rings he rushes to it and stands gazing around wistfully. The other morning his mistress went out to do her shopping, and suddenly remembered that she had left an expensive handbag lying on the couch. She rushed to a pay station & called her house. She let the phone ring half a dozen times then dashed for home, stopping at every pay station on the way to put in a call. When she got home the dog was sitting in front of the phone waiting for another call, and the handbag hadn’t been touched.

This wouldn’t work with Scout. He hides behind the washing machine when the cell phone dings.

I searched my 1942-3 index of letters (completed during Episode 5 production). Distraction, as published in The New Yorker, resembled a segment of Helen’s letter to Charles dated September 16, 1942.

I added comparing Helen’s letter to the similar content of The New Yorker article to the “For Later” List.’

James Thurber

I suspected the letter I found from Thurber to Charles dated March 27, 1945, was just the beginning of a thread I could follow about Thurber and my grandparents. I included reading a portion of the letter in Episode 4’s video.

What I didn’t read was the reference to one of my favorite Thurber stories. In the collection’s letter, Thurber shared that ‘Walter Mitty’, first published in The New Yorker, March 18, 1939, had been sold to the movies.

If Sam Goldwyn takes up his option. He wanted it for Danny Kaye.

March 27, 1945, Letter in the Another Thousand Letters Collection from James Thurber to Capt. Charles Cooke

Indeed Goldwyn did take up the option. Danny Kaye portrayed Mitty in the 1947 version of ‘The Secret Life of Walter Mitty.“

During my visits in the early 1970’s with Helen and in my English classes at The Ohio State University, Thurber had been described with reverence and awe. But, I did not have an understanding of his body of work. Nor did I know how close he was to Helen and Charles. It wasn’t until diving into this project that I learned they co-published many articles in The New Yorker. Even so, I had not researched their relationship further.

Exploring the possibility of additional correspondence between the Cookes and Thurber went onto my ‘For Later’ list. It was, you might imagine, tempting to return to Thurber’s archives held at my two-time alma-mater, The Ohio State University, in Columbus, Ohio. Correspondence, 1916 – 1974, from Cb – Cz circa 1930s-1960s, Box 41, Folder 7 looked especially interesting. Could “Cooke” be in there?

Distinguished Women of Washington, D.C. – Helen’s book

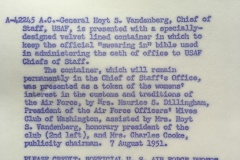

My connection to the Air Force Officers Spouse’s Club (AFOSC) continued. I found the club after noticing the labeled picture with Helen on the far left in Episode 2.

I connected with them by email during production of Episode 3 after which I looked for more photos. And in Episode 4, I included video of browsing Helen’s book, Distinguished Women of Washington, D.C. 1964, co-authored with Evelyn Dent Boyer. The last chapter featured Mrs. Hoyt Vandenberg. It contained several paragraphs detailing her work in reviving the AFOSC whose mission is in part to assure no service person is ever buried alone.

I added to my ‘For Later’ list providing an update about the club’s interest in the photos.

Playing the Piano for Pleasure – Charles’ book

The first file folder I investigated nearly fell apart as I retrieved it. Titled, “Letters from Amateur Pianists – Playing the Piano for Pleasure,” the folder contained dozens of letters from fans of Charles’ book. The first one I randomly opened and read was, coincidentally, from a woman in Columbus, Ohio.

Its three-page length delighted me as did its start: “Charles Cooke, You’re wonderful!” About halfway through, I slowed down to absorb the woman’s story. She had come back to the piano late in life after her father died. In an all too common story, she had set aside something she enjoyed because her family couldn’t afford lessons. But, Charles’ book, she explained, had revived the joy she originally had for the piano.

I heard her. We all give things up on our way through life. That said, I noted that this woman had started again inspired by Charles’ book. I wondered if he was as touched as I was. One letter like that from a reader can give a writer relief that all their work was worth it.

There were four file folders of letters from readers. I added indexing all of them to my ‘For Later’ list.

“For Later” Goldmine

The rest of the bin was a goldmine for the the “For Later” list. I ploughed through bin adding:

- Folder: Playing the Piano for Pleasure – Royalty Statements | How much did Charles make on the book? What was his book deal?

- Folder: Early Manuscripts | Manuscripts by Whom? What’s in this folder?

- Folder: Holiday Manuscripts | What’s in here?

- Folder: Original Manuscript of Playing the Piano for Pleasure | What should I do with this?

- Folders: New Yorker Stories

I couldn’t resist opening the ‘New Yorker Stories’ folder. And, I couldn’t wait for later to read the article, Moving Fingers, for which Helen received a letter from a “St. C McKelway.” He’d not only praised her work, paid her for it, and encouraged more, but also asked her to come into The New Yorker and talk about subjects. I was off to the internet to learn that McKelway was one of the magazine’s managing editors from 1936 – 1939.

More letters for the piano book followed as well as another folder titled, “New Yorker Stories.” The second New Yorker Stories folder had the “Three Little Pigs” article I’d found previously. The draft detailed Helen’s meeting with Roy Disney in New York to promote his movie.

That might be akin to my blog and YouTube channel going viral and Elon Musk coming by to promote his new Tesla monster truck. Who’d be huffing and puffing then, huh? Not by the hair of my chinny, chin, chin.

I digress.

I continued adding to the list:

- Who’s Who Booklets | What should I do with these?

- Simon and Schuster Folders | How many books did Charles pitch? What was a writer – Simon and Schuster relationship like? Was ‘Caravan’ Simon and Schuster too?

- Radio and Records | Are there radio recordings of my grandfather in an archive somewhere?

- Pocket Book Projects | What’s this? Does Pocket Books still exist?

- Piano Lessons

- The Étude Correspondence

- Keyboard – Correspondence

From Episode 3 to 4, my “For Later” list had increased from 5 to 27 items. I had unpacked everything except the letters. And it was to those I planned to go with Episode 5.

Enjoy the episode and please remember to like and subscribe. Thank you for following Another Thousand Letters.